Ability to study

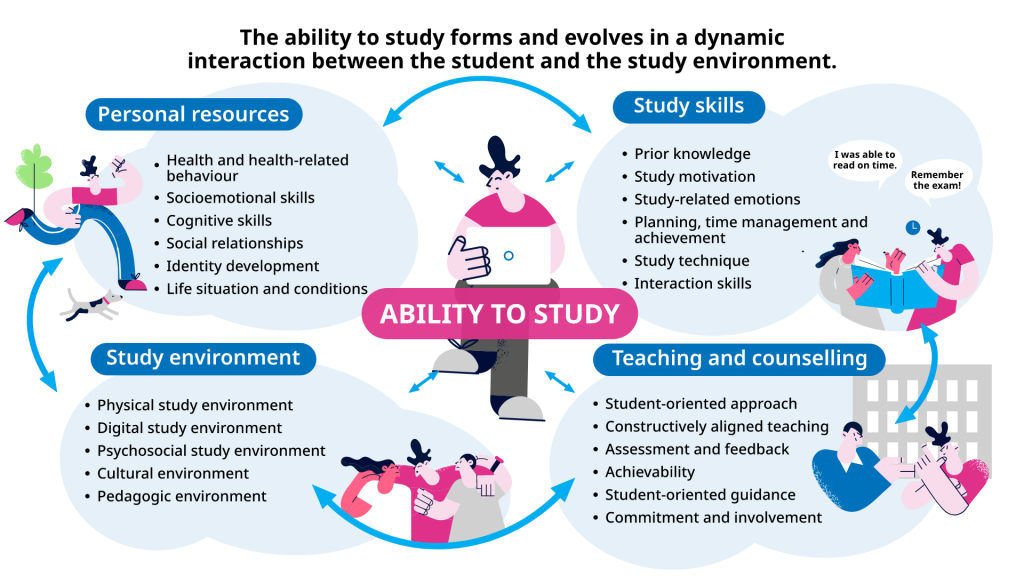

Ability to study means a student’s ability to work, and it’s a combination of several interconnected factors. Personal resources, study skills, teaching and counselling, and a supportive study environment all have significant impacts on how well a student performs. Strengths in one or more areas may help to maintain a student’s ability to study even when there are problems in other areas.

Study progress can be improved by addressing all the different aspects of ability to study. This is the responsibility of all parties in the study community, including student healthcare, the university and student organisations – and the students themselves!

The model for ability to study shown below can promote cooperation between different parties and at the same time support and help students progress through their studies. It can also help students to understand the different aspects of their ability to study.

The study ability model updated in 2022 is based on the model published by Kristina Kunttu (2006).

1. Personal resources

Health and health-related behaviour (click to open)

Our health is subject to change and the way we experience it is affected by illnesses, our physical and social environments as well as our experiences, values and attitudes. Health-related behaviour refers to the everyday health habits we have adopted. Health behaviour is affected by many factors, such as knowledge, skills, attitudes, expectations, beliefs, intentions, social norms and confidence in one’s own ability.

Good health is no guarantee of ability to study but at the same time illness is no obstacle to it either. Changes in other factors affecting ability to study can compensate for any impairment caused by illness. Poor health habits and addiction to intoxicants also impair ability to study.

Socioemotional skills (click to open)

Good socioemotional skills improve study motivation and prevent study exhaustion. Socioemotional skills change and can be improved throughout life. They include open-minded curiosity, tolerance, creativity, stress management related to emotional regulation, optimism, emotional control, as well as empathy, trust and cooperation when working together.

Cognitive skills (click to open)

Cognitive skills refer to functions related to the processing of information, such as attention, executive functions, linguistic and visual reasoning, and the different areas of memory. Learning and studying require many kinds of cognitive skills that can be practised. If there are clear problems in one area, strengths in other areas may compensate for them.

Cognitive skills vary from one person to another and can be affected by illnesses, brain injuries and age. Some people have clear learning difficulties that can have an extensive or a more limited effect on all areas of learning. Cognitive skills can be regarded as consisting of many different areas that interact with each other to lay a sound basis for learning.

Problems in one area of cognitive functions (such as trouble with reading or maths) can cause a lot of study-related stress, particularly in situations where these skills are very important. This may have an effect on the student’s wellbeing. The situation should be tackled at an early stage by discussing means of study support together with the student. Cognitive skills and learning difficulties can be examined by means of a psychological evaluation. When choosing a study field, strengths and weaknesses in cognitive skills should be taken into account.

See also “Prior knowledge” in the section on Study skills.

Social relationships (click to open)

Most people need social relationships for their wellbeing. The need for social relationships varies from one person to another and changes throughout life. A person’s social network may consist of many different communities, such as friends and family and work, study and leisure communities. Building new social networks can take time, especially in a new life situation, such as at the beginning of studies. Social relationships and means of communication have become more diverse with digitalisation, and people have their own preferences regarding them. Social relationships can also become a burden and cause a lot of anxiety and avoidance behaviour and this can impair ability to study, for example because of reluctance to participate in team projects. Sudden changes and crises in social relationships can temporarily impair a student’s ability to study. If the social network is supportive and readily available, crises can be easier to handle. Concrete support from family or fellow students can help to maintain ability to study.

Social skills can be practised. Safe social relationship that make you feel accepted and encouraged help to develop new skills.

Identity development (click to open)

Identity refers to a sense of integrity of the self and the continuum between the past, present and future. This sense is about committing to things like targets, plans and values and to engaging in different groups and communities. This gives direction and meaning to life and is essential for mental wellbeing. The second and the third decades in life are the most critical for the formation of identity, as the young adults become more independent and have to make decisions about their future. Failure to meet commitments, particularly those related to studies, or avoiding them altogether, increases the risk of exhaustion. The environment always affects identity, which is constantly changing.

Life situation and conditions (click to open)

Life situation and conditions at any given time have an impact on studies. Living conditions, a sufficient income and good, accessible public transport all make studying easier. As remote studying has become more common, access to digital tools and communications are increasingly important. Life situations and changes in them regarding things like family, health or becoming independent can be a resource or a burden in terms of studies. In terms of society in general, student life is also affected by political decisions related to livelihood (such as the study grant and housing allowance) and student benefits (such as the meal subsidy) as well as employment and future prospects. Over the past few years, environmental concerns such as anxiety over climate change have also become important issues for students.

2. Study environment

Physical study environment (click to open)

The physical study environment refers to built spaces and learning environments, which should be healthy, safe and accessible. Technology is a natural part of the physical study environment.

Digital study environment (click to open)

Technology is employed in creating the study environment, such as online courses and remote teaching. In today’s digital environment, the availability of digital equipment and networks and competence in their use are important, as well as equal opportunities regarding them. The digital study environment makes it possible to study remotely, which helps to balance studying and other areas of life.

Psychosocial study environment (click to open)

The psychological and social dimensions of the study environment are intertwined, as both are based on interactions between members of the study community and the quality of these interactions. A safe and supportive psychosocial study environment should have a good community spirit and emotional climate.

Most important is that students feel they are accepted, that their voices are heard, and that they are equal in every way, valued and psychologically secure. For this to happen each student should feel they are noticed, which in turn can be achieved if group sizes are sufficiently small and if teaching staff know them and address them by name. Also important is that they feel the teaching staff are readily approachable, easy to interact with and provide advice and guidance when it is needed.

Psychologically students can feel secure when they understand the procedures and ways in which their study community supports their commitment to their studies, provides help with difficulties studying and coping, and prevents or discourages them from dropping out.

The feeling of being part of the study community and different groups is important in the psychosocial study environment. Student organisations have a major role in strengthening students’ relationships and activities with their peers. Good peer relationships have been shown to promote wellbeing, to help students grasp the significance of their studies and to encourage them to continue. Tutoring and guidance from fellow students provide support for studies and social life and help students to integrate into the study community. Social support and trust between members of the study community help both students and the community as a whole to cope in times of crisis.

Cultural environment (click to open)

Cultural environment refers to values, attitudes and traditions in the study environment. These have a huge impact on whether students experience the study environment as equal, inclusive, diverse and open to everyone. Student organisation activities and in particular informal student events may involve norms related to traditions or culture that some community members may find discriminatory or exclusory.

Pedagogic environment (click to open)

Pedagogic methods and practices are employed in learning and teaching. See also “Teaching and counselling”.

Most degree courses involve work placements, and work experience is an important part of courses in social and welfare studies and educational studies. Good working conditions have a positive impact on the student’s wellbeing and the work placement experience.

3. Study skills

Study skills in general (click to open)

Higher education is about learning new things, expanding the understanding of our existing knowledge and even creating new information for the benefit of all mankind. The amount of information and skills to be learnt is often vast. As well as acquiring new information and skills, university students learn to establish their own identity and professional career. Students often find this motivating yet challenging. In order to learn new things, to take care of their ability to study and to progress in their studies, students need prior knowledge, study skills and the ability to reflect on their student identity. On the other hand, it’s the responsibility of the university to teach and guide students to identify their prior knowledge and to learn new study skills.

Study skills refers to the knowledge and skills that help students to progress in their studies and gain good results. Studying varies depending on the field of study, but there are some common study skills that can be identified.

Prior knowledge (click to open)

Learning new things builds on prior knowledge, and good prior knowledge is one of the best predictors of success in higher education. When students apply for places in higher education their prior knowledge is often tested through entrance exams or on the basis of their success at secondary school. Inadequate prior knowledge tends to become apparent at the beginning of studies. It’s particularly important that students have the required skills in reading, writing and arithmetic and a grasp of the basic concepts of their chosen field of study. Those who lack these skills may experience slow study progress, stress and problems with motivation. In terms of ability to study, it’s crucial that universities help students to understand their own competence level and give them a chance to address their lack of prior knowledge.

See also “Cognitive skills” in the section on “Personal resources”.

Study motivation (click to open)

Study motivation can be regarded as the force that encourages students to study. The reasons why students apply for a place in higher education and the related motivation are good predictors of ability to study. If the motivation to apply for higher education is either vague or poorly considered, the result may be failure to complete studies. Once studies have begun, the key motivating factor determining ability to study is the student’s confidence they will complete their studies. All teaching should encourage students to believe in their skills. A strong interest in the field of study and a desire to learn also support ability to study. A somewhat performance-oriented approach to studying is another important motivator affecting study progress. Students lacking it may often fail to achieve good results. The university can support study motivation by providing high-quality teaching and opportunities for peer support and a feeling of community.

Study-related emotions (click to open)

Studying is an intellectual and very emotional process. No matter how interesting the field of study, studying can be boring and exhausting at times. In such situations it’s important to manage study-related emotions to avoid apathy and impaired ability to study. Higher education studies may also cause anxiety, nervousness and fear. Anxiety over performance impairs ability to study, and dealing with it is an important study skill.

Planning, time management and achievement (click to open)

Studying in higher education means being independent and making one’s own decisions. The key study skills needed and developed in higher education are those related to self-management, such as the skills of planning, time management and achievement. Students should learn to monitor their learning progress, set targets and manage their activities accordingly. High-quality teaching with suggested timetables, course schedules, interim exercises and feedback helps students to make realistic study plans and stick to them. At the same time, students can learn the self-management and self-control skills required in higher education studies, which can require considerable independence. Good self-management and self-control skills promote a student’s ability to study.

Study technique (click to open)

A good study technique consists of elements such as self-testing, divided revision, formulating questions about the study material and finding answers to them, as well as discussing the study subjects and writing about them. It’s also important to understand teaching and assessment requirements and strategically adapt study techniques accordingly. High-quality teaching encourages students to engage in independent learning to expand their knowledge.

Interaction skills (click to open)

Communication and interaction skills are needed and further improved in higher education. They refer to the knowledge, skills and attitudes that enable students to interact effectively both in their studies and at work. Communication and interaction can take place in many different verbal or written languages, but non-verbal communication is also important. Good interaction skills help to make friends with fellow students, which in turn promotes communal learning, achievement, management of difficult study-related emotions and establishing networks in working life. For a minority of higher education students, studying is an independent journey during which they don’t really need other students to support their ability to study. But for most students communal studying is meaningful and helps them to prepare for working life. That’s why the teaching methods that promote communal learning are so important for ability to study and for skills in working life.

4. Teaching and counselling

Student-oriented approach (click to open)

Students’ experiences of their university are based to a large extent on how teaching and counselling are organized and implemented and what kind of culture the teachers and students create together. In higher education, pedagogy (i.e. the ways in which teaching and counselling are provided) is currently seen as student-oriented, which supports ability to study. It’s important to support interaction, community spirit and opportunities for students to have their say. This enables teaching to take into account each student’s abilities and helps to create a sense of meaningfulness, wellbeing and a commitment and devotion to studying. For motivation, it’s important that students feel they can influence their studies. High-quality teaching and counselling strengthen students’ belief in their own ability and take into account their individual characteristics.

Constructively aligned teaching (click to open)

The planning of high-quality teaching starts from the student’s point of view: what the student should be capable of and what teaching and assessment methods would best help in the learning process. We can talk about constructively aligned teaching, in which targets, course content, teaching and assessment methods are all consistent and encourage the deep processing of knowledge. Successful teaching and counselling motivate students and create a clear learning structure that is easy to understand. Students often say that they appreciate clarity in teaching. Curricula and teaching management play a key role in how students view teaching and counselling. As remote studying is nowadays common, online teaching methods are becoming increasingly important for students’ education and wellbeing.

Assessment and feedback (click to open)

Students themselves can both experience and influence the learning interaction during teaching and counselling through their participation, assignments and performance as well as assessment and feedback. With the help of assessment and feedback, students acquire an understanding of their subject and develop study skills such as self-management and emotional skills. The foundation for life-long learning is laid during studies. The assessment and feedback practices encountered during their studies should also help students to better assess their own skills and those of others and to understand the demands of their own particular field of study.

Achievability (click to open)

Achievability in teaching and guidance promotes everyone’s wellbeing as well as equality and fairness. Achievability in teaching and guidance means employing a variety of methods, that teaching material is accessible and that individuality and diversity are taken into account. In terms of ability to study, the assignments and achievements related to teaching should be such that students feel they can handle them and are able to acquire further knowledge and skills in their field. In case of challenges or impairment of ability to study, there should be enough guidance and support available.

Student-oriented guidance (click to open)

Different forms of guidance should be available to students, so that their individual needs and life situation in general can be addressed, if necessary. Guidance is provided in many different ways at different stages of studies. For example, the HOPS personal study plan and career guidance help with the overall planning of studies, while guidance relating to dissertations and theses aims to provide greater depth of knowledge in the student’s field of study. Student-oriented guidance seeks to make students more confident in their actions, more self-reliant and more active. Guidance helps students recognise and use their own resources so as to boost their independence and to expand and clarify their opportunities for action. Universities play a key role in providing students with information about different opportunities and ways to receive guidance, as well as the role of guidance in developing expertise and working life skills while studying. Awareness of the different forms and scope of guidance helps student to proactively seek the guidance they need.

Commitment and involvement (click to open)

Teaching and guidance bolster students’ experience of belonging to a community and their commitment to studying. Teaching and guidance create situations in which students form groups and become attached to the study community, familiarise themselves with their discipline and academic practices, work together and learn to function in a wide variety of peer groups. The ability to study together and receive study support from others is a key skill that can be improved by studying in guided peer groups, for example. Teaching and guidance should create safe and goal-oriented peer groups where students can reflect on and share their experiences, knowledge and skills as well as support each other in learning. Teaching programmes can have a major impact on students’ wellbeing and ability to study and consequently their study progress. A teaching programme should create situations in which teaching management, teachers, supervisors and students discuss and work together to create a thriving university culture.

The model for ability to study created by Kristina Kunttu (FSHS) and the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health was first published in a student health guide in 2006. The model for ability to study is based on the work ability model.

The model for ability to study has been in 2022 updated led by the FSHS. The purpose remains the same but the concepts have been updated to meet current needs. Institutions of higher education and student organisations were strongly represented on the working group in charge of the update. The founder of the model for ability to study, FSHS’s long-time Medical Director and Senior Researcher Kristina Kunttu, was one of the members, and there were also representatives from Nyyti ry and the KYKY project conducted between 2011 and 2014.

Members of the working group (click to open)

- Jonna Kekäläinen, Community Health Coordinator, FSHS

- Tommi Väyrynen, Chief Physician, Mental Health and Study Community Work, FSHS

- Elina Luoma, Psychologist in charge of mental health promotion, FSHS South

- Priska Autioniemi, Psychologist in charge of study community work, FSHS

- Kristina Kunttu, D.Med.Sc., Docent in health promotion, Senior researcher, FSHS

- Mikko Inkinen, Study psychologist, immediate superior for psychologists, Aalto University

- Ninni Kuparinen, Wellbeing policy advisor, National Union of Students in Finnish Universities of Applied Sciences (SAMOK)

- Petra Pieskä, Social Policy Adviser, National Union of University Students in Finland (SYL)

- Katariina Salmela-Aro, Academy Professor, University of Helsinki

- Riikka Suohurme, Study psychologist, University of Turku

- Viivi Virtanen, Principal Research Lecturer, Häme University of Applied Sciences (HAMK), EDU Research Unit

- Hanna Ahola, Expert in study-related wellbeing, University of Jyväskylä

- Heli Kiema-Junes, PhD, University teacher, Research center for psychology, University of Oulu

- Minna Savolainen, Executive Director, Nyyti ry

- Johanna Kujala, Social Relations Manager, Mieli Mental Health Finland

References

Study skills

- Richardson et al. 2012 Psychological Correlates of University Students’ Academic Performance

- Kim & Seo 2015 The relationship between procrastination and academic performance: A meta-analysis

- Waldeyer et al 2022 A moderated mediation analysis of conscientiousness, time management strategies, effort regulation strategies, and university students’ performance

- Asikainen et al 2020 Learning profiles and their relation to study-related burnout and academic achievement among university students

- Haarala-Muhonen et al 2016 How do the different study profiles of first-year students predict their study success, study progress and the completion of degrees?

- Telle Hailikari 2010 Assessing university students’ prior knowledge

- Westrich et al. 2015 College Performance and Retention: A Meta-Analysis of the Predictive Validities of ACT® Scores, High School Grades, and SES

- Korhonen et al 2019 Understanding the Multidimensional Nature of Student Engagement During the First Year of Higher Education

- Honicke & Broadbent 2016 The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: A systematic review

- Miller et al 2021 Achievement goal orientation: A predictor of student engagement in higher education

- Garn & Morin 2020 University students’ use of motivational regulation during one semester

- Pekrun et al 2002 Academic Emotions in Students’ Self-Regulated Learning and Achievement: A Program of Qualitative and Quantitative Research

- Roick & Ringeisen 2017 Self-efficacy, test anxiety, and academic success: A longitudinal validation

- Waldeyer et al 2022 A moderated mediation analysis of conscientiousness, time management strategies, effort regulation strategies, and university students’ performance

- Frazier 2019 Understanding stress as an impediment to academic performance

- Dunlosky et al. 2013 Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Technique

- Entwistle 1998 Approaches to learning and forms of understanding

- Asikainen et al 2020 Learning profiles and their relation to study-related burnout and academic achievement among university students

- Brouwer et al 2022 The development of peer networks and academic performance in learning communities in higher education

- MacCann et al 2020 Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis

Teaching and counselling

- Toom, A., & Pyhältö, K. (2020). Kestävää korkeakoulutusta ja opiskelijoiden oppimista rakentamassa: Tutkimukseen perustuva selvitys ajankohtaisesta korkeakoulupedagogiikan ja ohjauksen osaamisesta.

- Murphy, L., Eduljee, N. B., & Croteau, K. (2021). Teacher-centered versus student-centered teaching: Preferences and differences across academic majors. Journal of Effective Teaching in Higher Education, 4(1), 18–39.

- Postareff, L., Lahdenperä, J., Hailikari, T., & Parpala, A. (2024). The dimensions of approaches to teaching in higher education: a new analysis of teaching profiles. Higher Education, 88(1), 37-59.

- Biggs, J., Tang, C., & Kennedy, G. (2022). Teaching for quality learning at university 5e. McGraw-hill education (UK).

- Hailikari, T., Virtanen, V., Vesalainen, M., & Postareff, L. (2022). Student perspectives on how different elements of constructive alignment support active learning. Active Learning in Higher Education, 23(3), 217-231.

- Boud, D. (2021). Assessment-as-learning for the development of students’ evaluative judgement. In Assessment as Learning (pp. 25-37). Routledge.

- Molloy, E., Boud, D., & Henderson, M. (2020). Developing a learning-centred framework for feedback literacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(4), 527-540.

- Nieminen, J. H., Asikainen, H., & Rämö, J. (2021). Promoting deep approach to learning and self-efficacy by changing the purpose of self-assessment: a comparison of summative and formative models. Studies in Higher Education, 46(7), 1296-1311.

- Grimes, S., Southgate, E., Scevak, J., & Buchanan, R. (2021). Learning impacts reported by students living with learning challenges/disability. Studies in Higher Education, 46(6), 1146-1158.

- Nieminen, J. H., & Pesonen, H. V. (2019). Taking universal design back to its roots: Perspectives on accessibility and identity in undergraduate mathematics. Education Sciences, 10(1), 12.

- Alonso-Tapia, J., Merino-Tejedor, E., & Huertas, J. A. (2023). Academic engagement: assessment, conditions, and effects—a study in higher education from the perspective of the person-situation interaction. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 38(2), 631-655.

Study environment

- Yhdenvertainen ja saavutettava opiskelukulttuuri (opiskelukyky.fi)

- Kettunen, Roosa; Väntti, Maiju (2012) Opiskelukyky Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulun sosiaalialalla. Opinnäytetyö (theseus.fi)

- Ala-Nikkola, Riikka (2008) Masentuneen opiskelijan opiskelukyky ja opinto-ohjauksen tarve. Opinnäytetyö (trepo.tuni.fi)

- Jäppinen, Natalia (2020) Opettajaopiskelijoiden psykologisen pääoman suhde opiskelukykyyn. Opinnäytetyö (trepo.tuni.fi)

- Majoinen, Juha (2019) Toimintakulttuuri, resurssit ja pedagogia : oppilaan tukea edistävät ja vaikeuttavat tekijät fyysisessä, sosiaalis-pedagogisessa ja teknologisessa oppimisympäristössä. Väitöskirja (pdf, erepo.uef.fi)

- Hietainen-Peltola, Marke ja Korpilahti Ulla (2015) Terveellinen, turvallinen ja hyvinvoiva oppilaitos. Opas ympäristön ja yhteisön monialaiseen tarkastamiseen.

- Stringer Leigh, (2018) How the built environment can support Mental Health on Campus. Learning by design project (pubs.royle.com)

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Policy and Global Affairs; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Board on Higher Education and Workforce; Committee on Mental Health, Substance Use, and Wellbeing in STEMM Undergraduate and Graduate Education; Scherer LA, Leshner AI, editors. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Wellbeing in Higher Education: Supporting the Whole Student. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2021 Jan 13. 3, Environments to Support Wellbeing for All Students. Familiarise yourself with: Environments to Support Wellbeing for All Students – Mental Health, Substance Use, and Wellbeing in Higher Education – NCBI Bookshelf (nih.gov)

- Rusticus, S.A., Pashootan, T. & Mah, A. What are the key elements of a positive learning environment? Perspectives from students and faculty. Learning Environ Res 26, 161–175 (2023). Familiarise yourself with: What are the key elements of a positive learning environment? Perspectives from students and faculty | Learning Environments Research (springer.com)

- Anteroinen, Henna & Nikku, Annika (2022). Naisopiskelijoiden kiinnittyminen tekniikan alan opintoihin suomalaisissa yliopistoissa. Pro gradu tutkielma (erepo.uef.fi)

- Saarinen, K. (2020) Oppimisympäristö oppimisympäristössä. TAMK-konferenssi – TAMK Conference 2020. Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulun julkaisuja, Erillisjulkaisuja, s. 96–103 (pdf, theseus.fi).

- Lindfors, Eila (toim.) (2012) Kohti turvallisempaa oppilaitosta! Oppilaitosten turvallisuuden ja turvallisuuskasvatuksen tutkimus- ja kehittämishaasteita. (pdf, trepo.tuni.fi)

- Porevirta, Laura, Pätynen, Iida (2021). Yksilölliset ja yhteisölliset tekijät opintojen alkuvaiheen kiinnittymisessä. Pro gradu tutkielma (pdf, jyx.jyu.fi)

- Makkonen, Mari (2022). Vasuagentit varhaiskasvatuksessa: Varhaiskasvatuksen tutoropettajien kokemuksia. Pro gradu tutkielma (trepo.tuni.fi)

- Puttonen, Sami (2018). Kansainvälisten opiskelijoiden integroituminen korkeakouluyhteisöön. Pro gradu tutkielma (trepo.tuni.fi)

- Opiskeluterveydenhuollon opas. Helsinki 2006. 249 s. (Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriön julkaisuja, ISSN 1236-2050, 2006:12) ISBN 952-00-2026-8(nid.), ISBN 952-00-2027-6

Personal resources

- Salmela-Aro, K. Upadyaya, K. Ronkainen I & Hietajärvi L (2022). Study burnout and engagement during COVID-19 among university students: The role of demands, resources and psychological needs. Journal of Happiness Studies.

- Guo, J., Tang, X., Marsh, H., Parker, P., Basarkod, G., Sanhdra, B., Ranta, M. & Salmela-Aro, K. (2022). The roles of social-emotional skills in students’ academic and life success: A multi-informant, multi-cohort Perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

- Salmela-Aro, K., Upadyaya, K., Vinni-Laakso, J. & Hietajärvi, L. (2021). Adolescents’ longitudinal school engagement and burnout before and during COVID-19: The role of socio-emotional skills. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31, 796-807.